The following was written in 2002 shortly after our journey to Sarajevo to visit our friends Arthur and Elena, who were working in that distressed city at the time. The images and commentary were published on my website as separate galleries but these were subsequently lost or degraded. This is an attempt to resurrect what turned into a travel diary, using my original words which reflect the impressions made on me at the time by the various cities on our route.

Berlin

In March 2002, during a long rail trip across Europe, we found ourselves with one day to spend in Berlin, a city we had never visited before. It is impossible to do justice to such a place in such a short time and we decided to limit ourselves to visiting places we had heard of before our visit.

The Reichstag is a massive and impressive building, though perhaps a little ponderous and heavy. At this time it was in the centre of a complex of redevelopment and surrounded by cranes and building sites.

A brisk northerly wind, and frequent showers of sleet, limited the time we were prepared to admire it and so we cross the Unter den Linden and walk through the Tiergarten, back towards the Zoo Station. The noise of the city is muffled by the tall stands of mature trees and apart from a few joggers and dog walkers we meet no one. In the years after the First World War, while employed by the Prussian Academy of Sciences, Einstein walked along these very paths and in the quiet gloom of the wood, it is easy to imagine a solitary figure striding past us, head down, lost in deep thoughts and muttering himself, something about God playing dice. It is a pleasant walk. We see heron and buzzards and numerous ducks on the various streams and ponds. The trees are showing the very first signs of spring, a yellow green fuzz and from the thick carpet of leaves, daffodils and other flowers are pushing through. We decide that on a day like today we prefer the Tiergarten to the Reichstag.

We travel to Friedrichstrasse Station and walk along Unter den Linden. It is a cold gray day with flurries of sleet. The Cafe Einstein catches our eye. In some book about the great man I had read that, during his period in Berlin, he had enjoyed strolling in the Tiergarten and drinking hot chocolate in a cafe on the Unter den Linden. Perhaps this is the one! It is also a very cold day and a hot chocolate seems an excellent idea. It is expensive but very good, a theme that can be applied to much of Berlin. The cafe has a formal, old fashioned atmosphere. The tables are marble topped, the waiters wear black suits and the hot chocolate comes rich and hot with a large mound of whipped cream.

Outside again, ahead of us, we can see the Brandenburg Gate. At least that what we thought we were looking at. On closer examination we realise that the monument is covered by an enormous canvas screen on which its image has been painted.

Close to the Reichstag, we stop to examine the Russian War Memorial, a massive structure with columns and steps, set in an area of parkland and adorned with field guns, tanks and a huge statue of a Russian soldier. The slate grey skies and sleety rain do nothing to reduce its cold, impersonal character. Though it does have a grim, stark sort of grandeur, nothing can do justice to the enormous losses it was built to represent. It is a sad and empty place.

This reminded me of magazine and film images from Berlin at the end of the war; its surroundings a testament to man's ability to recover and rebuild. This nineteenth century church was destroyed by allied bombing in 1943. The surviving tower, with strong echos of Coventry Cathedral, was incorporated into a modern church building in the 1960s.

Towards the end of our Berlin day we buy a very late lunch, which consists of an "American Wrap" bought from a sandwich stall, which we eat rather self-consciously on the U/Bahn.

Continuing our policy of visiting Berlin sites most known to us, our lunch is taken on the way to Check Point Charlie, both of which live down to our expectations.

The film of the book "The spy who came in from the cold" has Richard Burton attempting to escape through a drab urban landscape to the safety of the border checkpoint. The area has lost none of the depressing seediness I remember from that desolate closing scene.

Prague

It is not just in London that one can see the changing of the guard.

Our impressions of the cathedrals we visit are painted with a broad brush. They dominate their surroundings even today and it is difficult to imagine how overwhelming they would have seemed in the midst of fourteenth century buildings. We are not experts in architectural styles and can absorb only so much historical detail before it begins to run together into a half remembered blur. After a few days only vivid fragments of the whole are left to be recalled. St Vitus' left me in awe of the craftsmanship necessary to produce such complexity of detail, to create such a soaring space and work on the beautiful vaulted ceiling, with the equipment then available, so far above the ground. This vast tranquil space has the power to absorb school parties yet still seem mainly empty, reducing even their chatter to a reflective respect.

Crossing the Vlatava from the Old Town to the Mala Strana (Lesser Quarter) is the wonderful Charles Bridge. It was built in the fourteenth century from large sandstone blocks and is surprisingly wide. The parapet is lined with statues and impressive fortifications guard each end. Even during the ninth hour of the day and still only March, it is crowded. There are artists, buskers, traders and beggars - a whole community of varied enterprise - competing for our attention. But the greater part of the hustle and bustle comes from the endless school parties: straggling knots of noise and vitality, anxiously shepherded by weary adults, their heads forever turning to check the numbers.

After crossing the Charles Bridge and following a rising cobbled street we enter the complex of Hradcany (Prague Castle). Inside this we are confronted by the magnificent St Vitus' Cathedral. For a photographer there is no good view of the cathedral from inside the castle. No shot takes in the whole building or captures the impact of being suddenly close up to this soaring, intricate structure. There is a stance from the rear from which it is possible to include the whole building in one view, but in front it is better to concentrate on the details which are many and impressive. The best distant views of the Cathedral are from across the river or from Peltrin Hill.

During our final hours in Prague we return to the Charles Bridge and I attempt some night photography, using the stonework rather than a tripod to cope with the long exposures. It is quieter now. Most of the stalls and buskers have gone, but there is a steady stream of late evening walkers and the beggars - a sad, disturbing spectacle - remain at their post.

Budapest

Several bridges join Buda and Pest across the Danube. This is perhaps the most attractive and with much less traffic, a more pleasant crossing place on foot. After a short walk on a quiet and intensely cold Sunday morning, through the centre of Pest, we make our way back to the river, close to the Parliament Building. Here the attractive Chain Bridge or Szechenyi Lanchid crosses the river. This is a much more people friendly bridge and we pause for a while, despite the continuing cold. Below us the river is high and pushing hard against the two towers that hold up the chains from which the bridge is suspended. The water, a steel blue roiling mass of enormous power, reflects the sky. Behind us, on the Pest side, are the gothic extravagances of the Parliament building. Ahead is Buda, which presents a more dramatic face to the river with castles, cathedrals and palaces, sharply etched and glistening in cold sunlight, crowning its hills.

From the Chain Bridge we can see ahead of us on the Buda side, Castle Hill dominated by the magnificent Matthias Kirk. In front is the Castle, now a museum and seen to the left is the extraordinary Fisherman's Bastion.

We climb up the Castle Hill to a wide terrace, swept clear of other visitors by the chill wind. In the centre of this open space, huddled miserably in a long black coat, is a solitary figure. As we approach he pulls a violin from beneath his coat and begins to play a few tentative notes of some very familiar gypsy tune. We are not disposed to stay and enjoy this sound and continue on. As we leave his sphere of influence, the music forlornly dies away only for another strolling musician, who had been sheltering unnoticed next to a wall, to begin another gypsy air. Again we continue and silence resumes. In the distance we hear our first musician strike up again and shortly stop. There are several more of these stubborn unappreciated violinists in the area, each defending his territory with sound, like robins in a garden. In more clement conditions no doubt, they help create a lively atmosphere for strolling visitors to enjoy: but today it is brisk walking that is called for.

From the terrace we take photographs of the fine views of the river and its bridges with the parliament building and the rest of Pest beyond.

The Parliament building, occupying a riverside site, in all its Gothic splendour, has distinct echos of Westminster in London. Build between 1890 and 1902, with some difficulty on the soft silt of the river bank, the building houses the offices of ministers of state and the Prime Minister.

A gentle stroll south of the castle, where it is a little more sheltered, through a series of medieval fortifications and parkland, brings us to the Elizabeth Bridge and the foot of Gellert Hegy (Gellert Hill). At the top of this 235m hill is the Citadel, an interesting white stone fortification, and by repute, the best vantage point of all for viewing Budapest. There is also a comprehensive guide to the history and archeology of the hill, from the Bronze Age to the present and the provision of English descriptions of the exhibits encourages us to spend quite some time taking it in.

Although it is a cold day, the air is like glass and and the skies are bright. It is perfect for enjoying the view of the city and the river. The Elizabeth Bridge links Buda (right)to Pest in the foreground. Beyond is the Chain Bridge and in the distance the Margaret Bridge which mkes use of the tip of the island of the same name to link the two parts of the city.

The Matthias Kirk takes its popular name from King Matthias, but is more properly known as the Church of our Lady. It was started in the 13th century and its building continued until the 15th century.

In 1541 Budapest fell to the Turks and the church became a mosque for a while until it was recaptured and became a Jesuits' Church.

In the 19th century the church was partially rebuilt in the Gothic style. At the same time, on the site of a former fish market, the extraordinary Fisherman's Bastion was built close by.

Zagreb

We arrive late one Sunday afternoon in Zagreb, for an overnight stay en route to Sarajevo. We have a few hours to explore and find somewhere to eat. The bitter cold is not made more bearable by the gathering darkness. In the centre of the city the streets are narrower and the buildings older. The shops are all closed and there are few people about until, round a corner we are suddenly confronted by a large crowd and lights. Bizarrely, we have stumbled across the start of a marathon, a fact proclaimed by a large sign strung across the road. There are forty to fifty runners lined up, shivering and jumping on the spot to keep warm, officials in blazers with clipboards and cameras are all around to record the event. The gun fires and the runners surge forward only to pull up after thirty yards.

"Cut!" shouts the director, from an elevated position on top of a jeep. At least, that is what I assume he said. As we move on, wondering what film or TV progamme it is all for, he seems to be assembling the runners for another start.

We wander around the streets for another half-hour, finding a large square. There are several cafes and bars, but none display menus and the people inside are drinking rather eating. Where do the people of Zagreb go to eat out on a Sunday night? At last we find a fish restaurant down a side street and enjoy a cuttlefish risotto with salad. I had wanted to order a fillet of local Lake Balaton fish but had been put off by what appeared to be its incredible price. Too late I realised that the prices quoted are per kilo and not per portion. The risotto, jet black in colour, proved extremely tasty and washed down with a local riesling made a good meal.

One further misunderstanding awaited us on our way back to the hotel. In the afternoon I had taken a photograph of a very attractive square which was lined with huge eucalyptus. Now the trees with their smooth, silvery bark are lit by floodlights and, it seems to me, provide the opportunity for a dramatic photograph. We stop at a seat where I set about making a long exposure, using my camera bag as a makeshift tripod. Unfortunately, we are about forty yards from the gates of the U S embassy, which, at this sensitive post 9-11 time, is guarded by armed police. We are quickly surrounded and asked to explain ourselves. They are rather impatient with my vision of the scene's potential, but seem to conclude we are mad rather than dangerous. Tonight I have learned the Croatian for, "Cut!" I believe I now also know the Croatian for, "Fuck off!"

The railway system of Bosnia Herzegovina is largely derelict. There is but one scheduled train, which leaves at nine o'clock each morning from Zagreb Glavni Kolodvor, for Sarajevo, and there is a return service from there at the same time. It leaves from platform four, a platform which is not, as you might expect, between platforms three and five, but off to one side, as though the services operating from here are separate and nothing to do with the busy, efficient comings and goings in the rest of the station.

There were two trains waiting at platform four. On the right was a short train of three, ancient green coaches, of the open saloon type, with two hard upright benches facing and back to back down each side of the coach. The ends of each coach were open verandas, of the sort seen in American cowboy films. It looked very, very uncomfortable and we were not entirely sure, at first, that this was not to be our means of reaching Sarajevo.

Fortunately, the Sarajevo train turned out to be the other one: a train of seven or eight more modern, though well worn, blue coaches, with a corridor and compartments, pulled by a neat orange and blue electric locomotive. One of the compartments had been converted into a small buffet. This seemed more acceptable for a nine-hour journey.

At nine o'clock, the train moved off heading south through the suburbs of Zagreb and then through the tidy but unremarkable countryside of central Croatia. The train ambled southwards and eastwards, with the River Sava someway off to the left, stopping at each small town. The border between Croatia and Bosnia Herzogovina is on the River Una, a tributary of the Sava, which itself eventually joins the Danube. Here the train stopped and there was a customs examination. The smart orange Croatian locomotive was detached and an ancient, rusting diesel shunter replaced it. This pulled us no more than half a mile across the bridge, to the separate powerlines of the Bosnian system, where another electric locomotive was waiting. A new set of customs inspectors came on board and there was a considerable wait. In a siding next to our train, a line of ore carrying wagons were standing where they were left, perhaps as much as a decade ago when this land was being fought over and the united Yugoslav railway ceased to operate. Grass is growing up between the tracks and the wagons are orange-brown with rust. It was an unsettling and depressing sight.

We had arrived early and were first on the train. It never got very full but most compartments had one or two people in. Just before nine o'clock, a tall, white haired man joined us. It was difficult to assess his age for his face was lined and stressed. He was dressed in a dark suit, but gave the impression that he was not comfortable in such clothes. He could have been a struck-off doctor who had fallen on hard times or a workman in his only suit, on the way to a funeral. We nodded at each other but did not speak. As the train got closer to Bosnia, our companion was preoccupied. He seemed unable to sit still. He took documents out of his case and examined them. He stood in the corridor for a while, smoking; then returned to his seat, leaning forward, wringing his hands. I thought I heard him groan. As we approached the border and during the crossing formalities, the tension in our companion increased. He began to make a strange, low, wailing sound as he sat with his elbows on his knees and his head in his hand. In some alarm, I realized he was quietly chanting some prayer or song to himself. He seemed agitated and depressed.

After about forty minutes at the border the train, without any sign or warning, started to move again. And almost at once we began to see destroyed buildings. It was not whole areas of devastation, just a few houses here and there, or little groups which had been selected for destruction and, although we had been expecting to see this, it still had the power to shock. It was clear that something awful has happened here. Our companion was visibly affected and groaned, this time clearly. Suddenly, we had some understanding of a possible cause of his distress and in our minds he became part of the tragedy we could see, passing the window of the train.

At Dobrijn, the first stop in Bosnia, our companion gathered his things together and left. As he turned to slide the compartment door closed behind him, our eyes met. He nodded again, gave us a sad smile and was gone.

What part, we began to speculate, had he played in the region's recent history? What terrible things had he seen or maybe even done? We decided that, perhaps, he was a refugee, returning home for the first time to see what was left of his home. We will remember that face.

From Dobrijn the line follows the River Una for a while, as far as Novi Grad, before swinging eastwards towards Prijedor and Banja Luca and other names given a sinister resonance by remembered items of news. The weather was poor, with flat, gray skies and persistent drizzle that gradually gave way to sleet, then snow as we climbed higher. The train clanked gently along at no more than forty miles per hour, which permitted, for a while, the lowering of the carriage window for a more intimate view of the scenery and brief moments of contact with life along the line.

A dog pauses for a moment as he paces his yard and looks straight at me. There is nothing hostile in his gaze and I sense that, if I was able to leave the train for a moment, he would be happy to let me pat him and a gentle word would cause his tail to wag. He watches with seeming interest as the train passes by. It is probable he does not see many passengers leaning out of train windows. He is chained up outside on a cold wet day, though with the option of finding shelter in his kennel. Perhaps the passing of the daily train is a regular diversion for him. It is likely that he does not get a lot of human contact. This is a working farm and he is a working dog, there to give warning if someone approaches or guard the other animals. Somewhere there is a cow or goats, which graze the ubiquitous conical haystack. Every farmhouse had one, sometimes reduced to a mushroom shape by the animals eating out the lower layers.

There is nothing quaint or pretty about these farms and smallholdings.It is a noticeably untidy landscape. This seems to be a country with no system of waste disposal. There are piles of rubbish every where, in settled areas and in open country. Abandoned cars, some half hidden by invading vegetation dot the landscape and the streams, in spate due to the spring rain and snow melt, are disgusting with plastic which hangs in dirty sheets from every twig and root.

These sorts of images had maximum impact around the town of Banja Luka, the heartland and capital of Republica Sirpska. This is where General Vladic and the former President Karradich, both indicted war criminals, are said to be hiding out. It occurred to us, as we surveyed the grim scene from the station (from now on, when I hear a place described as a hole or dump, Banja Luka will be my standard) that it would be a cruel and unusual punishment to be trapped indefinitely in a place like this and it does not really matter if they are caught or not. Perhaps a sort of justice is being done by leaving them be.

Although we observed ugly, man made details like the litter close to the track, the countryside was, at the same time, quite beautiful. After Banja Luka, the track climbs steadily and soon we were in a land of forests and mountains interrupted now and then by small villages. We began to see a new feature: the slender towers of the mosques began to replace the squatter outline of the churches. There was no other discernible change. The houses and the farms looked exactly the same, whether they were in a village with a mosque or in a village with a church.

A little further up the track, when the sleet and drizzle had given way to genuine snow, we saw a man driving a horse and cart across the field with a load of hay; no doubt on his way to replenish one of the haystacks we had been seeing everywhere. It was a picturesque, timeless image. We had no idea whether he was a Serb or a Muslim.

Sarajevo

Top of any "Must see" list in Sarajevo is the place where the Archduke and his wife were assassinated in 1914, triggering World War 1 and determining the entire course of European history since. The Archduke's open top car, having got lost, was attempting to turn right off a bridge across the Miljakka River, now called the Princeps Bridge after the gunman. It stopped by chance only feet from the would-be assassin who had at this point given up any thought of being able to find his proposed victims. He could hardly miss.

It is obviously a site of immense significance. But not to the people of Sarajevo! The only sign that anything of any consequence whatsoever has occurred at this spot is a small wooden post. Originally this had had some information written on it, but the label has been vandalised and ripped off. I confess to some surprise that so little is made of this site, but perhaps that is just a different form of chauvinism. Princeps was a Serb and the event reflects no glory on Bosnia or Sarajevo. And besides, at the moment they have bigger problems to worry about.

The event occurred on the far side of the bridge in this view.

In the old part of the city is the exquisite Ali Pasa Mosque, built in 1560, of rich creamy limestone. It is the oldest mosque in Bosnia.

In the same area as the Ali Pasa Mosque is the Turkish market. This is a large area, unchanged since it was built in the sixteenth century, of narrow streets lined with stone built stalls, some with windows open to the outside. An overhanging roof shelters the pavement which is smoothed and polished by almost five centuries of passing feet. It is very much a place to amble through slowly, browsing the shop windows and enjoying the atmosphere.

Chess is a great leveler. In the square outside the Orthodox Cathedral, both Muslims and Christians give the game their full attention.

The Post Office tower has been heavily damaged while the Holiday Inn has escaped relatively unscathed which perhaps explains why it was much favoured by journalists during the siege.

More shell damage in the centre of Sarajevo.

This is a view from the slopes of Mount Igman, looking down onto the city. The houses and villages up here have all been destroyed during heavy fighting. Large stretches of the pine forest have been reduced to shattered stumps and, as though still shocked by the experience, show little signs of re-growth. The ground is pock marked by earthworks and shell holes. A few years earlier the Serb forces would have been defending this place as they laid siege to Sarajevo. From up here they could see right into the heart of the city, drop a shell where they wanted and their snipers could pick off people on the streets at will. This place, more than any part of the city itself gave me some insight into the nature of their ordeal.

Bosnia-Hercegovina is a land disfigured by hatreds. In normal times, in the areas where the population is homogeneous, the hatred is profound but dormant: it is a part of the shared assumption of what it is to be a Muslim, or a Croat, or a Serb; a grim relishing of historical grievances; comforting because familiar. Where the territories meet and overlap there is a sullen acceptance of the existence of the different group and a mutual live and let live agreement. There is no love, but in quiet times pragmatism prevails. In a few special places, where the three groups have lived profitably together for centuries, the hatreds have melted and diluted, so that the people think of themselves as of that place, rather than of a particular group. Once Sarajevo was such a place.

In more dangerous times the loathing of those who are different, even in the unmingled heartlands where attitudes are not informed by direct experience, can overflow into bloodshed. An easy route to power in such times is to feed and inflame the bigotry. The history of Bosnia-Hercegovina is littered with leaders who have followed this path.

Much twentieth century history turns on events in Sarajevo, but more recently, the world's attention has been focused here for two very contrasting reasons. It was here that Torvil and Dean skated their way to an Olympic gold and from where Kate Adie, candle-lit and in her flack jacket, broadcast dramatic war reports from the Holiday Inn.This descent from enthralment to horrified incredulity is the result of ethnic rivalry, the curse of this region. The tragedy of Sarajevo is that it could not avoid becoming part of the disaster taking place around it, with each group answering the call of its own. Friendship, tolerance, cooperation and sharing counted for little once the flood of ethnic violence reached the walls of the city.

As a result, the city was attacked and blockaded. To cross a street like this during the siege of Sarajevo, was to risk sudden death from a sniper's bullet

In the hills above Sarajevo are these memorials to a happier time and the Winter Olympics. But even here we could pick out bullet holes in the concrete structures.

Sarajevo

After our stay in Sarajevo, Arthur and Elena took us to Dubrovnik for a short stay, before we took the ferry across to Italy and the start of our journey home. I think we were lucky to visit Dubrovnik when we did. By all accounts today it is mobbed, choked with cruise ships and impossible to move around. All that had barely started in 2003.

This is a view of the old part of Dubrovnik from the hills south of city. It shows the red roofs of the houses, punctuated by the towers of churches, surrounded completely by a high defensive wall.

Dubrovnik is sometimes referred to, with some justice, as the "Jewel of the Adriatic". Its origin lies in the seventh century and throughout its long and turbulent history, it has been an important port and trading centre with links across the Mediterranean and beyond.

Much of the old walled town was rebuilt following an earthquake in the seventeenth century. What makes it so special is its completeness and homogeneity. Indeed, to walk through the gate under the tall limestone walls, into the handsome squares and streets, is to feel, for a moment, like stepping into a film set of some historical romance.

The modern part of the city contains a large commercial port, but the Old City Port is more for fishing and tourism. Behind the harbour the walls of the city rise up to a handsome tower.

Dubrovnik was besieged for several months, following the break up of Yugoslavia in 1990. Serbian forces occupied the surrounding hills and sporadically shelled the city. the old town and its walls suffered some damage but there is very little trace of that today. The building to the right may be one of the last pieces of rebuilding.

Everyone who visits Dubrovnik will walk around the city walls. This provides a wonderful view of the city itself and of the coast to the north and south. The buildings within the city walls are very much working homes and the walls often allow a very intimate view into attractive courtyards and gardens. This old canon guards the entrance to the harbour below.

This is a view from the walls on a Sunday morning. This beautiful street, called the Stradun or Placa, is full of citizens promenading in their best clothes or on their way to church.

The Stradun is paved by rectangular blocks of crystaline limestone, which have become polished by centuries of wear and seem to have acquired a translucent sheen.

No doubt, in season, (this was early spring) it will be crowded with tourists rather than natives, but it was nice to see that, beautiful though Old Dubrovnik is, it is not merely a tourist spectacle, but a genuine working town and home to people with other occupations.

From the harbour a small boat can take you across the bay to the beautiful island called Lokrum. This is a fascinating place and well worth a visit.

There was once a monastic community here and traces of their labours can be seen everywhere in the variety of flowers, fruit and trees that grow here. The monastery buildings are complete and very attractive, with cloistered squares and gardens. The monks left behind their cats which now greet every arriving boat in great numbers.

A gentle walk around the island, on paths laid out by the monks in the shade of the trees, is a pleasant way to pass an afternoon and provides another fine view of Dubrovnik.

Another view of the attractive Old Harbour.

Rome

For our first ever visit, we reached Rome by a roundabout route - by ferry from Dubrovnik and by train from Bari - giving us just four days to experience what we could. The sites known to us and most prominently advertised in the tourist brochures determined our itinerary, with time so short.

This policy soon brought us to Rome's most recognisable landmark, the Coliseum. Built by Emperor Vespasian in 80AD, it is still an awesome structure and one, which is impossible to photograph in a fresh original way. We paid our 8 Euro entry to the grumpiest ticket seller in Italy, a man who obviously hates his job and who creates a queue by refusing to give change and by operating very slowly. He also failed to reveal that the ticket to the Coliseum is also valid on Palatine Hill, an omission that later cost us another expensive entry charge.

In early April the monument was not oppressively busy and it was possible to move around freely. The wide stairs connecting the different tiers to the entrances reminded me very much of a large football ground, designed to allow a large number of people to leave quickly and safely at the end of the entertainment.

St Peter's and its environs occupied us for a whole day. This perspective is from Pont St Angelo. It is a breath taking, extravagant spectacle whether viewed inside or out. Whatever one's personal belief, this building is impressive and makes a strong statement of confidence, wealth and power.

Emperor Constantine erected a basilica here in the fourth century, possibly on the site of the tomb of St Peter. The present building dates from the sixteenth century. Michael Angelo was one of the architects and is responsible for the magnificent dome which dominates the scene. In front of the church is St Peter's Square and the dramatic colonnade built by Bernini.

Inside there are intricately detailed carvings everywhere and rich decoration, but what most impresses is the vastness of this cool dark space that seems to swallow up the largest crowds. As we walked slowly around, absorbing the atmosphere, a group of young Americans began to sing in four part harmony beneath the dome. As this sweet unexpected sound rose up into emptiness, the background murmur of low voices and shuffling feet died away as everyone paused, touched by beauty of their music - a lovely, lovely moment.

Towards the end of the day when the queues had diminished, I climbed to the top of the dome to enjoy the view. This is the scene looking back towards the Pont St Angelo with the Castel visible just to its left. St Peter's Square and the colonnade are spread out below under the gaze of the statues of the apostles.

Climbing the dome is quite arduous. I did not count the steps but there were enough to necessitate the occasional pause. The dome is actually two mutually supporting domes with a space between them. It is through this space that the narrow passage to the top spirals upwards, leaning inwards slightly. Having stood beneath the dome, looking up, I was vividly aware of how much space was directly under my feet. I felt distinctly uneasy leaning inwards against inside of the lower dome. "How much weight will the dome bear? How much do all these people climbing with me weigh?" were the sort of thoughts that crossed my mind. Such ideas are dispelled on reaching the top where one of the best views of Rome is the reward.

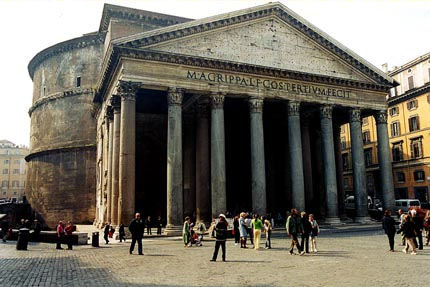

The Pantheon is a recycled Roman temple that has been consecrated as a Catholic church. Beyond the classical porch and through the huge bronze doors is an enormous circular space, topped by a self supporting dome. The only natural light into this area comes from a circular opening or oculus in the centre of the dome. As the sun moves round, a shaft of light sweeps the interior illuminating different parts, creating fascinating lighting effects as the hours pass.

In spite of the crowds of tourists passing in and out of the church, a wedding was being conducted in a roped off area. The bride and groom were kneeling before the alter while the priest was some way off at a lectern, going through the ritual and seemingly ignoring the couple as well as the hundreds of curious passing on-lookers. We found it a bit strange and impersonal.

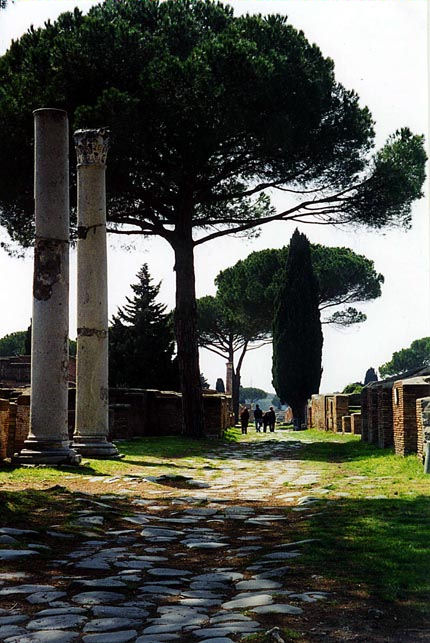

In the end we found Rome a bit too much. After three days of traffic, crowds and noise, and an endless succession of spectacular things to look at, we had reached saturation point. We decided to get out of Rome for a few hours and visit the excavated Roman port at Ostia. Ostia Antica can be reached very cheaply using the metro. Tickets are priced by time not distance and one ticket validated for seventy five minutes was enough to get to there.

It was a bright Sunday morning and very quiet and peaceful. It was very pleasant to amble along ancient Roman streets, in the shade of the umbrella pines. There were shops whose wares are still advertised by the mosaics showing fish or fruit and grain in front of them. We sat for a while in the seats of an almost intact ampitheatre and wondered what had been performed on the stage below. It is a very large site, the main street stretching for half a mile or so and there is much to see.

Venice

Venice is scruffy, falling to bits and probably a bit smelly in summer. We loved it! We arrived by train from Rome and the approaches are not inspiring. It is flat, built up and industrial. Then the train crosses a long causeway and enters Ferrovia Venezia San Lucia into a different world. Leaving the station is a memorable experience: before you is a flight of broad steps leading down to the water of the Grand Canal, to the left is a bridge which is immediately familiar, across it is Venice in all its medieval splendour, exactly as you have always imagined it.

The first lesson when visiting Venice is to stay on the island rather than the mainland. The former is magical and expensive, the latter cheaper but very ordinary indeed. The best way to get around is to take the waterbuses or Vaporetti, which go everywhere and are cheap and frequent. Spectacular views of all the famous landmarks can be enjoyed from the water. This is the landing place for St Mark's Square, followed by a shot in the square. To the right is the Doge's Palace and behind that is St Mark's Basilica. The magnificent brick tower is the Campanile of St Mark's, all some of the most visited and photographed places on earth!

In Venice people, goods indeed everything moves by water. This view of the Grand Canal from the Rialto Bridge shows a variety, but by no means all, of the types of craft we saw during our stay. There seems to be the aquatic equivalent of most types of road vehicles, as well as boat jams and canal-rage.

On one occasion we heard the wail of an approaching siren from a side canal and I waited for a police boat, with which we were already familiar, to appear. To our surprise a water ambulance leaned round the corner at great speed into the mass of boats on the Grand Canal. Some how it managed to avoid a collision and sped away before I thought to raise my camera. There is also a water-borne equivalent of "white van man". These transport a variety of goods on barge like vehicles that are steered aggressively close behind other craft until they make way.

During the first few hours of a visit to Venice, a photographer will be ever raising his camera. Every view is worth a shot, or several, until the appetite is over-sated and the shutter finger in danger of RSI. (Not another sixteenth century basilica!) But some sites never become too familiar because they can be viewed from so many different angles and in a variety of lighting conditions.

This one of dozens of views of the Church of La Salute, built between 1631 and 1681; beautiful inside and out.

The Rialto Bridge is one of only three that cross the Grand Canal and most people will therefore walk across it and sail underneath at least once on a visit. It is another much photographed landmark and dates back to the late sixteenth century.

Venice is sufficiently compact for it all to be accessible on foot. Away from the main canals is a maze of narrow passages, squares and alleys, laced with narrow canals crossed by many bridges. You will get lost! Very easily! But don't panic. Eventually we noticed that there are frequent discreet little signs that point either to Ferrovia, Rialto or San Marco. With these essential navigational aids and a map we were soon finding our way about.

This view is typical of Venice off the beaten track. I have absolutely no idea where it is. We were still hopelessly lost at the time.

Innsbruck

There are three ways of traveling through the Brenner Pass. There is an ordinary road, an extravagant motorway that is carried high above the valley floor, but seems to isolate the traveler from the environment and high on the other side of the valley, (right in this view) and far more discreetly, runs the railway line between Italy and Innsbruck.

It was the railway that brought us from Italy to Innsbruck - by far the best way of making the trip, in the opinion of one who has tried them all. Sitting at the back of the long train, watching the coaches curving ahead behind the bright red locomotive, there was one moment when I suddenly exclaimed, "Good heavens, there is another train down there!" being fooled for the moment by the steeply descending, curving track. Unlike the brutal structures that carry the motorway and dominate the scenery, the railway is more sympathetic, hugging the slope and curving in and out with the folds of the ground. It is an exciting ride.

Innsbruck is a pleasant place to stay. Particularly attractive is the Old Town, which has narrow streets, and small squares lined with medieval houses.

The Hungerburgbahn is one of the last remaining funicular railways in Europe. From close to the old city centre it carries the visitor across the Inn and up to the attractive Hungerberg plateau. This connects with the bottom station of the cableway up to Nordpark-Seegrube and a final leg that reaches the summit at Hafelekar (2334 m.) In winter this concerns only skiers. In summer, mountaineers and hill walkers benefit.

Public transport in Innsbruck can only be described as wonderful, not least because of its fleet of vintage trams. We visited Hungerberg by bus. At every stop, waiting passengers are kept informed of the destination and expected time of arrival of the next two or three services. On the bus an electronic screen displays the name of the next stop and how long the journey will take. Why can't we have services like that?

Innsbruck is a twelfth century market town, which began where a bridge (brucke) crossed the River Inn. This view of the city, taken from the top of the cableway at Nordpark-Seegrube (1905 m.) shows the town spread out across the valley floor. The River Inn, milky white with glacial sediment, winds away to the east, eventually to join the Danube. To the right the entrance to the Brenner Pass can be seen behind the motorway viaduct.

Innsbruck was the site of the winter Olympics in 1964 and 1976. Close to the line of the motorway the ski jump slope, redundant at this time of year, can be seen

The line from Innsbruck to Munich via Garmisch-Partenkirken provides one of the world's great railway journeys, most particularly the first half of it. The line leaves Innsbruck and climbs and climbs. There are tunnels, cuttings, viaducts and amazing views. It is one of those lines, which climb the side of a mountain by corkscrew-like tunnels from which the train emerges to reveal the track it was on a minute or so ago, several hundred feet straight down.

After the climb the line traverses more gentle valleys, lined by dramatic peaks and passes through a succession of pretty, Alpine villages. This view taken through the window of the train is near Garmisch.

The rest of our itinerary requires a little explanation as we do not take the most direct route home. We called in at Innsbruck because we had once visited it before and liked it very much. Strasbourg has always sounded exotic and exciting because it is a stop on the Orient Express route. We turned south to Lyon so that we could come back on a TGV to Paris which at that time was our first experience of high speed trains. Brussels was our final stop before heading to Amsterdam and the ferry home.

Strasbourg

The name Strasbourg must have occurred many times in lessons on European history - a crossroads of Europe, a city on the Rhine, fought over by France and Germany. Certainly it was filed away in my mind under "exciting", ","distant" and "important", a place I have always meant to visit. It did not disappoint.

Actually it is not so much on the River Rhine as the smaller River Ill, the older part of the city being built on an island formed by this river and several canals. There are so many canals here that in some ways it seems almost Venetian.

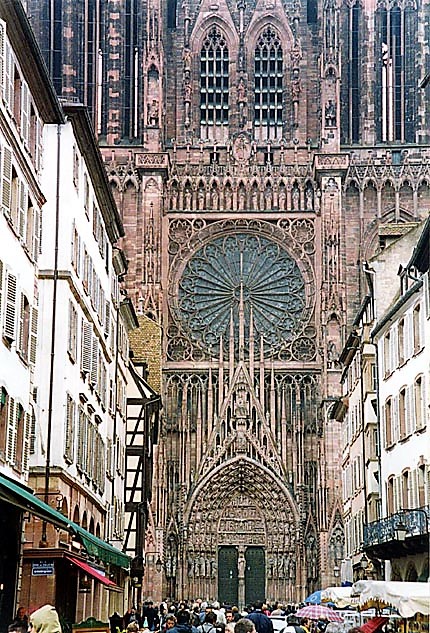

This is a view of the Ponts Couvert, with their extraordinary three medieval towers, located at the tip of the island, called Petite France, where the two branches of the river join together again. Behind, dominating the whole island, indeed the whole surrounding area of Alsace, is the Notre Dame Cathedral, one of the most impressive medieval buildings I have ever seen.

It is not possible to see the cathedral in its near vicinity; the streets are too narrow and the buildings too tall. Then suddenly round a corner, there it is in front of you - this enormous wall of intricate, magnificent pink stonework. I know of no other gothic cathedral that has the same sort of in-your-face impact.

There was a cathedral begun here in 1015, but the present building was rebuilt starting in the late thirteenth century. When the tower was completed early in the fifteenth century this was the tallest building in the Christian world. A record it retained for the next four hundred years.<br.

It is not possible to climb to the top of the tower today but it is well worth climbing up to its base for a stunning view of Strasbourg and the surrounding landscape. Evidence of earlier visitors can be found carved into the stonework. W. Pratt of London 1835, and hundreds of others recorded their passing in ways that are not tolerated today.

Close to the Cathedral, in the Old Town there are attractive squares and narrow streets, enclosed by medieval timber framed buildings. Even on a cool, wet Sunday morning in spring there are groups of tourists receiving a guided tour.

The combination of timber framed houses, canals and quiet canal side paths makes Strasbourg an enjoyable place to amble around.

One of the reasons that Strasbourg is pleasantly free of traffic, relatively speaking, is that in 1994 it reintroduced an extensive light railway or tramway system.

And what trams! Once again I found myself in a European city and wondering why Britain cannot afford such superb public transport. Perhaps it was thought that the home of the Council of Europe and the European Parliament deserved such a system and Strasbourg received a little help.

I am delighted to report that, twenty one years later than Strasbourg, Edinburgh now has a limited net work of similar trams!